A better understanding of what the program and each course was going to focus on: practical skills versus theory.

As it said in the inspirational article above, "library schools could better communicate to students exactly what parts of their education are intended to target" each. These are professional masters degrees so a certain amount of both is required: we need to be able to both do the job and know why we're doing it so we can maybe do it better. It would be ideal if every course, regardless of subject had a clear balance of each. In my experience, some courses had it and others didn't, and my school seemed to particularly focus on the practical skills when I was yearning for more theory.More education on the collections management side.

My current position (and previous position, and probably several future positions) is in collections management and other technical services functions. Sure, I had a reference resources course but having worked with resources, vendors, publishers and all the technology involved, I've found that I've had to learn much of it on the job. Part of the problem is certainly the fact that electronic resources were still pretty young in 2001, but I don't recall learning anything about the publishing industry, in general or regarding specific players. Evaluation of resources would have been very useful, even in general principles since they shouldn't have changed that much despite the resources themselves changing.More information about the details of the library school's focus.

A not-too-recent blog entry stated that "it really does not matter which library school you attend". I beg to differ. It might not matter whether you come from a "top rated" school or not (although this article basically says that it's pretty much the only thing that matters in most fields), but there are certainly differences between library schools that, when I was applying and for many years after graduating, I didn't know at all. But in speaking with colleagues from various institutions, particularly ones that were actually smart enough to look into the matter before handing over the tuition dough, library schools can differ greatly. Some are best for producing mass quantities of just general librarians, whereas others are more suitable for those looking to continue on with a PhD; some have a great Archivists' program, while others are better for public librarians. Perhaps this has changed since I was really looking into choosing a school, but, just like with any institution of higher education, marketing yourself as a solution for everyone when you aren't isn't good for you or your students.Don't worry about making the argument for the program being a good investment or not.

Honestly, this was never really a concern of mine but I see it more and more in higher education. I'm not sure a Master of Library and Information Science program or the like could be described as a good investment (sometimes yes, sometimes maybe, sometimes no) but I'm not sure it really matters. Heading down a career path shouldn't be considered in the same way as sizing up stocks and bonds. Deciding to take a certain academic or professional program that tends to lead to a certain career is all about whether YOU will be able to at least live with it if not enjoy it. You don't have to like the company that you're investing in, at least not as much as you're going to have to like the job you may be doing for the rest of your life.Make it less about books and more about information.

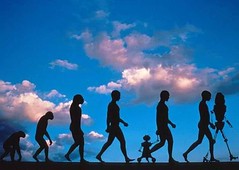

Yes, I know that we all like books (see the first paragraph from "So You've Decided to Go to Library School"), but we shouldn't be basing our choice of a profession on such a stereotypical understand of what librarians do. Libraries are, and always have been about more than just books. Yes, we can take advantage of the public's seemingly permanent connection between libraries and books, but if we don't make a bit of a connection with other things, then the second society loses their love affair with the dusty old tomes, we're toast. In fact, in some libraries, books aren't even the thing the collections budget is spent most on. I would like to see more focus on the Information part of the MLIS than on the Library part. Don't get me wrong, I like that it's in the degree name (I don't like the MIS or the, shudder, MI) but I would gladly get rid if it if that's what it took to make our profession a little more respectable.Ok, so I've had my rant. What do you think? What would you change (or not) about librarianship education?